>>SELECTED CRITICAL REVIEWS<<

... "Social Fabric" is Trasobares's latest commentary on consumption,

institutional excess, Cuban politics, and sexual appetite. An artist, curator,

collector, and

art activist, Trasobares has worked in Miami for three decades. He's shown

here and elsewhere and his output has remained constant. Yet Trasobares

is not as

well-known as he should be and his own artistic independence may have to do

with it. He prefers to keep art separated from business to be free

to engage in social

discourse.

"His mix of tension and sarcasm resembles Marcel Broodthaers's appraisals

of the art market. Broodthaers, the late Belgian conceptual artist, created -

like Trasobares - conspicuous museum like displays. In addition a "surrealist" Cuban-exile

touch can be discerned in Trasobares's critique. "Social Fabric" is

a protest, a paradox, a slip-of-tongue, a combination of Pop and satire.

“… Though invested with a more overtly political agenda, Elian

in Wonderland (1972-2001),

by Cesar Trasobares, also destabilised any self-contained notion of 'art'. Like

some parallel version of Jeremy Deller's archiving of British

folk art, the installation was the result of almost thirty years spent

collecting hundreds of objects from Miami's large right-wing, Cuban ex-pat

community. This period culminated in what was the focus of the collection: the

furore surrounding the repatriation of Elian Gonzalez. Amongst the wall-pinned

photographs of protesters, anticommunist banners, and T-shirts proclaiming

Janet Reno's thralldom to Castro, were cabinets containing home-made

crucifixes, ugly Clinton caricature dolls, and mutilated Action-Man figures

dressed in Nazi uniforms with Stars-and-Stripes patches. Trasobares's

curatorial project negotiated a fine line between appreciation for these

cultural artefacts and censure of the lunatic sentiments behind them. …”

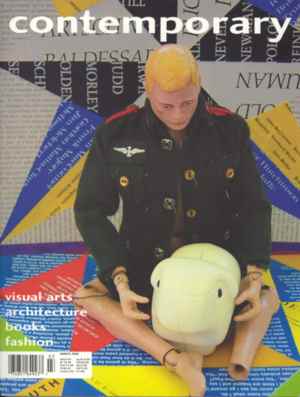

Gabriel Coxhead, reviewing globe>miami<island

Contemporary, March 2002

“… An exhibition within an exhibition is Cesar

Trasobares's Elián in Wonderland, a multifaceted installation displaying

trinkets of all sorts, cheap figurines, toy soldiers, Barbies and Kens, along

with original

posters, from the Elian days and -- just for the opening -- a live young model

inside a fish tank with two inflatable dolphins. It's a microcosm of Cuban

culture, nationalist kitsch, and caustic analysis worth more than any textbook

on the subject. …”

Alfredo Triff, “Take a Bow …” Miami New Times, 3-9 January 2002

“En 1983, Christo "envolvió" once cayos de Miami

en un gesto formidable y bastante sorprendente. Sobre todo si tenemos en cuenta

que lo hizo en una ciudad en la cual, tanto entonces como ahora, el arte y la

calle están radicalmente divorciados. (Incluso podría decirse que el kitsch de

la galería —abundante tambien— no es el kitsch de la calle). Unos aĖos antes,

César Trasobares habia seguido un camino inverso si bien con propósitos similares.

En una de las indagaciones más interesantes que se han realizado sobre la

cultura popular y visual cubana en Estados Unidos, Trasobares realizó su serie

de quinceaĖeras

a finales de los 70, junto a varias perfomances encaminadas a quebrar

la división

apuntada entre el "arte" y la ciudad. Este artista, además, dirigió

como comisionado público un proyecto urbano que representó a Estados Unidos en

la Trienal de Milán de 1988, dedicada a las ciudades.

Posiblemente, Trasobares y Christo hayan ejecutado los

actos más importantes por hacer del arte en Miami una "cosa pública".

De paso, sus proyectos se dirigieron a activar el discurso visual de una ciudad

—más bien un archipiélago urbano— a la que Europa o parte de los propios

Estados Unidos han acreditado como una capital del "easy money", el

turismo, el kitsch latino, en otro tiempo del narcotráfico, de la segregación

racial o del anticastrismo (todo eso, a veces, explosivamente unido), pero no

como una capital del arte o algo por el estilo. Entre el gesto de Trasobares

—llevar la estetica popular a la galeria para resemantizarla— y el de Christo

—realizar un environment fuera de la institución convencional e implicar a la ciudad— medió el

arribo, por el éxodo de el Mariel, de varios artistas y escritores, quienes

portaban una diferencia estética, racial, sexual y cultural considerable con

respecto a lo que estaba acostumbrado a asumir y consumir ese Estado. Así,

cuando tiene lugar la redefinición del arte en los 90, esta no parte de cero.

…”

Iván de la Nuez, “Redefiniciones en los 90,” LAPIZ, December 1996.

Cesar

Trasobares has ingeniously rocked the status quo throughout his far reaching

career as an artist and art activist. Born in Cuba and bred in Miami, he began

deconstructing the iconography of exile culture in his conceptual artworks back

in the Seventies, long before Cuban imagery had achieved its current trendy

status. The local market encourages painting, but Trasobares expresses himself

with needlepoint pillows carrying messages that critique the art world,

sexually evocative ready-made objects, imaginary designs for teenage girls’ quince

dresses, and

elaborately-drawn diagrams of museum administration hierarchies. As executive

director of Metro-Dade’s Art in Public Places program from 1985-90, Trasobares

left our local landscape a legacy of works by Edward Ruscha, Richard Haas,

Carlos Alfonso, and others. He has served on numerous national curatorial

committees, grant panels, and NEA boards, always advocating the basic need for

(uncensored) art in America. A staunch supporter of younger artists, he

encourages them to defend their creative freedom. Trasobares is what an artist

should be – an active citizen. He is our choice because we admire his artwork,

but also because he tries to make Miami a better place for art.

Judy

Cantor, “Best Local Artist,” Miami New Times

22 – 28

June 1995

“…in

the CFA lobby, Miamian

Cesar Trasobares has installed Museum of American Democratic Art: Tumbling

Chairs, which poses this question: Do

American museums represent another sort of "fragile ecology"? Taking

the canvas directors chair as his metaphor, Trasobares (a keynote speaker at

Thursday's opening of the ninth conference of the National Association of

Artists' Organizations) suggests that museums have become the locus of

colliding forces, interests and agendas. He piles up 60 chairs in a pyramid,

their backs identifying the seat of power each represents, with "DlRECTOR:

Museum Marketing" at the top and these elsewhere in the pile --

"CURATOR: Blue Chip Artists," "WOOER: Artists' Estates,"

"TRUSTEE: Latino Powerhouse," "CONSULTANT: Global

Esthetics" and even "V.P.: No Food, No Drink." The seats of

every chair are screened with the M.A.D.A. logo in Gothic script, including the

phrase "showcasing the gorgeous mosaic of our cultural fabric." Remind

me never to use any of those words again.”

Helen Kohen, reviewing the exhibition, Fragile

Ecologies and

Trasobares’ installation at Center for the Fine Arts,

The Miami Herald, 1 May 1994

"… In a more critical

vein Cesar Trasobares' installation explores the social rituals of Cuban

culture such as the Fiesta, a ball in which a 15 year-old girl makes her

society debut and displays her talents. White dresses embellished with beads or

sequins and empty picture frames evoke the disordered atmosphere of an

old-fashioned attic after the ball. On the wall are collaged, framed mementos -

fragments of gloves, purses, jackets, and other costume pieces presumably worn

on these occasions that constitute portraits of people or situations related to

these celebrations. On the wall beside these framed assemblages, fragments of

conversations are inscribed: 'Does he come from a good family?' 'Are they

upper-class?' While the glitz and glitter of these festivals are clearly

celebrated, there is also a sense of 'framing,' almost as if the artist were a

sociologist or archaeologist recording ... viewpoint of most Cuban Americans

encountering this exhibit. This postmodern consciousness has the curious effect

of showing the artist who lives between two cultures as already self-conscious

and alienated from his own cultural experience. This sense of 'otherness' is a

constant undercurrent of this exhibition. …"

Cris Hassold, Review of "Cuba-USA: The First

Generation", Art Papers, January 1993

"… Other artists take a more ironic stance vis-a-vis

Cuban customs. Take the work of Cesar Trasobares, a Miami painter turned

cultural anthropologist. His subject is the life and times of a fictional

character he calls Rosata QuinceaĖera. She is the quintessential Miami Cuban

girl whose coming of age at 15 is celebrated with an elaborate and expensive

party known as the Fiesta de Quince. A combination debut, talent show and

heritage festival, the Quince often requires professional choreographers and second

mortgages. Trasobares simultaneously parodies and memorializes this Cuban

potlatch. His fascinating collages combine programs, mementoes and clothing

-tuxedoes and frothy white formals--with trinkets, photographs and newspaper

clippings in a poignant portrait of what he calls "a dying modern

ritual."

Mary Abbe, "A Potent Mix of Cultural Symbols:

CUBA-USA Show Views Are Unique," Star Tribune, 2 February 1992

"...Trasobares...

takes this opportunity 'to chart my own trek out of the ghetto' of Cuban-American

art. He transforms the ball gowns of the quinceaĖera into the materials of a

raft, that powerful political symbol for Cuban exiles, The walls around the

craft are painted to suggest a map of Cuba, a sea and swimmer emerging free of

the water, and everywhere there is graffiti, 'What Cuban art?' Trasobares

writes on a supporting column, which, he says, marks his 'transition from the

residual of a Cuban background to free space.' What appears to be a statement

about Cuban-American politics is really about art politics. ..."

Helen Kohen, "Cuba-USA: Enormous Exhibition by

Artists Who Left Their Homeland Offers Viewers a Look at the Face of

Miami", The Miami Herald, 3 May 1992

"...Cesar

Trasobares revels in the miniature. His massive collection of rings, from the

souvenir glitter of 'Texas Engagement Ring' to the fine carving of an African

ring, has inspired his art. This former director of the Metro-Dade Art in

Public Places sees rings as intimate and infinitely various cultural artifacts,

signs of the wearer's power or allegiance to other people. They encompass many

meanings: 'I find a ring in almost anything,' he says.

In his installation at Gillman are several glass cases

full of his collected rings and those he has made. Some strike arty witticisms,

including his 'Ed Ruscha' ring, bearing the message 'Such Read.' It's an

anagram of the name of that artist, whose word paintings include those circling

the rotunda of Miami's Main Library. Another, a tiny soft sculpture a la Claes

Oldenburg, is printed with stock market quotes - a soft market indeed.

The show gives us a look at Trasobares' mercurial

imagination, his puns and wry jokes. Some jokes carry an activist edge,

including the cast copper art soldier, a toy-sized GI Joe armed with books and

paper. While the rings and soldiers can make their points quickly, Trasobares'

poetic drawings stand out. Images of rings, maps, and even newspaper clippings

about rings are layered over pale washes of color that briefly describe land,

sea and sky. They are dreamy charts of experience, comparing the artist's role

to a rafter navigating risky currents limning the globe."

Elisa Turner, "Gillman Show Takes a Circular

Tack", The Miami Herald, 27 November 1991

"Cesar

Trasobares is the one artist in the group who confronts the bicultural

situation absolutely head-on, in a piece from his 'QuinceaĖera' series, The

work is a shrine-like assortment of elements from the real world - Cuban and

American flags, a striking white gown of the kind a 15 year-old Cuban girl (a

'quinceaĖera') might wear to her coming out celebration, a few scrap-book

mementos - combined with a veiled collage composition that hints at secret

pleasures or pains or disappointments..."

Benjamin Forgey, "The Cuban Evolution", The

Washington Post,

14 June 1984

"The ritual of the quince is rooted in powerful

assumptions about the relationships between the sexes. The material in the

exhibition that simply documents it is often the most interesting, because of

the intricacies of personal theater and public fantasy it exposes. In the 'Las

Chaperonas' series, Trasobares has succeeded in transforming his documentary

material into art, perhaps because he has distinguished the superficial from

the profound aspects of the ritual and the relationship it formalizes... "

Paula Harper, "Exhibit Pokes Fun at the Quince", The Miami News,

15 June 1984