MIRALDA'S TOUCH:

FROM PRIVATE NOTES

TO ARTE PUBLICO

Inventing projects to be carried out in public spaces, Antoni Miralda was

a public artist before the practice became fashionable among artists in the

late

1970s.

He learned to think and plan his projects through his private notes and

drawings. As author, choreographer and master of ceremonies, Miralda had

to convince

himself of the tone and rhythm of each event and project. The components

and directions

of his site-works had to be developed, recorded and explained through

drawings and verbal directions to the numerous players in his orchestrated

artworks.

At times, the projects had to be presented to sponsors and public officials.

In

all cases, the drawings served multiple purposes. For the audiences who

did not see them, the resulting artistic actions were linked to remote places

and

times, to fleeting episodes and occurrences as in music and dance performances.

Our connection now to the thinking behind those public ceremonies, performances

and installations are the drawings in this book. Taking great risks as

an artist by producing ephemeral site related work, Miralda developed

his ideas

and images

on paper, but he never really intended many of these images and notes

as more than personal working documents. In addition to some formal presentation

drawings,

many private drawings were “rescued” for their first public

presentation here. Although some of the drawings embody private thoughts,

most of them

relate to works of public art.

While much of the reality of public events is evanescent, some of their

flavor, genesis and sources are still preserved in the drawings, in surviving

monuments

and in the images and case histories in this book. Thus, in a historical

sense, these drawings reveal the workings of the artist's mind, the emergence

and evolution

of ideas and forms, and especially for the unrealized projects, their

sole existence.

Working in the public realm in our times requires that artists be explicit about

the components and timing of their projects. Workers have to be cued and trained,

fabricators have to be directed, sponsors have to be convinced and motivated.

Beyond the emergence and evolution of the artist's ideas we also see here the

rhetoric of the artist's intentions and his use of drawings to present, explain

and convince. We also view the magic of visual and verbal representation, the

interplay of squiggle, ideogram, pictograph, letter and word. We witness the

near-chemical emergence of a position, a gesture, a movement and their evolution

into images and language.

The public art terrain in which Miralda operates remains an exposed frontier

of culture clearly functioning in other terms than the conquered cultured

parcels of art museums and the uncharted but protected corners of the art

world. In many

ways, in these drawings we also witness the artist's definition of his

territory, the carving of the social space for artistic intervention, the

stretching of

the conception and boundaries of the work of art. Each site-specific

event was sculpted by Miralda in collaboration with a group of performers/participants,

every time in a different circumstance, always charged with the passion

and thoughts

of the presenters and the audiences, saturated with the emotions and

momentum of each environment. This book places Miralda's work on the border

of ancient

traditions of public ritual and at the forefront of the evolving movement

of public art in the last half of the twentieth century.

The approach to inventing, selecting and siting public art in Europe and

in the United States has evolved significantly in the last four decades.

From the

earliest attempts in the 1960s at placing large studio works outdoors,

through the collaborations between artists, architects, engineers and other

professionals

of the 1980s, to the more recent political engagement and action of artists,

the notion of public art has been radically challenged and re-examined.

As the drawings and case histories show, Miralda was pushing the boundaries

of this

unexplored territory, risking at times the perception that his work

was some kind of glorified ritual, facing the sceptical questioning of his

work as

legitimate and relevant art.

In all of his projects Miralda was firm and clear about his esthetic intent,

at times relying on his historical awareness, intuition and informed

imagination, whether he was functioning alone or with a group of bakers

or cheerleaders, always

recognizing the practical and philosophic differences between working

in a public environment versus the private realm of the artist's studio.

Even

when

laboring

with other artists or with craftsmen, Miralda acknowledged and respected

his co-workers' esthetic potentiality, joining them in their own forms of

self-expression.

This

serious attitude and approach as a public artist led him to value an

adaptive method of artmaking that is formally and imaginatively responsive

to an audience,

a place, its history, context and use. Unlike the isolated practice of

traditional studio-artists, today many artists are embracing and welcoming

a broad

public into all aspects of their art. With Miralda the audience and the

co-workers in any project were an integral component of the artwork since

his first

Fête

en Blanc.

Many of the scenarios exposed in presentations and publications about public

art do not sufficiently emphasize the fact that the artist is the central

focus of any art production, that the artist is the one taking risks and

assuming responsibility

for the total work of creation. In addition to his/her vision and concepts,

an artist producing a work of public art must consider what is realizable

with limited

resources, what is allowed by commissioning entities and public agencies,

what is possible to construct in compliance with building codes and standards

of public

safety, what is accepted by increasingly vocal public audiences, what

is vulnerable to political interference, what is realizable under the overused

covers of artistic

freedom.

Beyond these factors, more elusive conditions play important roles in public

art: the willingness of patrons to provide support and funding to complete

artworks without compromise, the cooperation of sponsors and bureaucrats

in re-interpreting

guidelines to accommodate flexibility and possibility, the complicity

of art writers and critics in supporting public art and in presenting this

type of expression

in its own terms. Even when the artwork was itself the subject of the

interests of sponsors, whether as an image for public relations or marketing,

Miralda

acknowledged the changing interpretations and transformation of the meaning

of his works as

their images transcended the boundaries of his own intentions. Permeable

to the porous contours of culture, Miralda has been an astute player in all

of his works

that have actually materialized, especially those staged in the United

States. In the few instances where sponsors attached too many strings and

conditions to

their support, Miralda firmly stated his convictions, opting to decline

producing a project compromised and changed beyond his purposes.

And yet, having crisscrossed and charted the public territory in Europe and in

the United States, Miralda can also be an intensely private artist. The earliest

drawings done in a modest sketch book in military camp explore the actual profiles

of figures and uniforms. His studies for the Projet pour un banc

de square, the

re-alignments of images from military manuals, the permutations of soldier images,

all become obsessive personal commentaries on social structuring and strong statements

against war and aggression.

In his early work, Miralda was also an avid appropriator of images, especially

in the many works which include toile de jouy, and the Essaie

d'Amelioration executed on historical posters. He was also a willing collaborator with

other artists, becoming involved in all aspects of a project or exhibition,

including

the design of many of his exhibition announcements. His posters and unlimited

edition postcards extended his images and ideas into the public realm

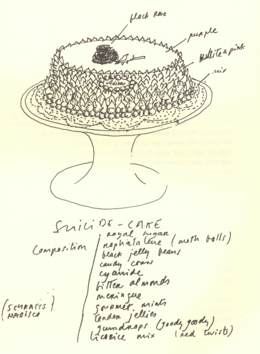

of the mails. In contrast, the Suicide Cake provides a recipe an individual

or a group's

fatal ritual.

Other drawings include choreography annotation, descriptions of unusual materials,

recipes of all kinds, menus, alignment of marchers in a street parade,

elaborations on techniques of coloring bread or rice. Some drawings reflect

upon the history of art (Venus Bolero) while others celebrate popular

culture, imploding political and gustatory territories (Coca-Cola Polenta).

Themes like the Last

Supper appear as a set of postcards in the Mercedes Benz Last Supper,

eventually becoming encoded in other projects. Drawings for numerous tables

show the artist's

ever expanding conception of one of mankind's most universal pieces of

furniture: appearing in multiple geometric guises and also broken, exploded,

forming a labyrinth,

jutting into the Mediterranean Sea, elongated like a serpent, shaped

like an airplane, becoming a double-tailed mermaid.

As Miralda explored food for humans and deities through the years, he also

developed events of all types, served famous food to animals, worked with

Montse Guillen

on a showcase restaurant, El lnternacional, engaged and married statues,

concieved monument-gifts from various cities to his famous couple. All of

this is included

here, at times embryonically, at times in full illusionistic splendor.

Drawing as a way of recording persons and objects, drawing to actualize reality,

drawing to probe his mind for images, drawing to capture the fleeting

inner commentary, drawing to resolve technical and logistical details of

a project,

drawing as

a means of documenting other versions of an artwork, drawing to seduce

a potential sponsor, drawing to comply with bureaucratic requirements: all

these

have been

employed by Miralda in the three decades of work shown in this catalogue

of the artist's instruments.

Drawings in military camp, in trains and planes, in New York, Miami and Barcelona,

drawing in Paris and Berlin, Miralda has faced the empty page with simple

pens, pencils, markers, sometimes a little watercolor or the occasional shadowy

smear

of his own saliva. This book contains a major selection of the artist's life

work, revealing a range of expression and invention, exposing the nervous

garabato which becomes a black swan or a marching figure in a parade, embodying

a dizzying

imagination which conceives, rethinks, enlarges, revises and executes. Flipping

through these pates viewers see the artist testing his ideas, adjusting initial

modes, shifting directions and refining the ever-evolving structures and

forms.

These extended uses of the language of drawing, beyond the prevalent perception

of a drawing as the means of recording of visual reality, of the drawing

as “finished

artwork” for the art market, of a drawing as the history of a moment

of inspiration, are manifest here. The artist focuses his draughtsman's

tools on

a locus of potentiality and invention; his drawings become the record,

the evolving imaging of directed aesthetic formalization, its history

and his

probing.

Miralda's arsenal of drawings expose a linguistic and semiotic exploration,

revealing to a broad public a form of private communication and the substance

of his search

for a public esthetic. Beyond their relation to the many projects and monuments,

the images speak volumes for themselves, awakening and strengthening in all

viewers a belief in the power of drawing as a universal, timeless language.

As a fundamental

means for the artist to deal with his artistic vision and his inner and outer

reality, the drawings in this book embody the struggle and the record of

Miralda's universal public art and fascinating private quest.

Cesar Trasobares

Miami, September 1994

Cesar Trasobares, an independent artist and

art activist based in Miami was Executive Director of the Art in Public Places

program in

Dade County, Florida (1985-1990), one of the pioneer programs of public

art in the United States. Trasobares worked with Miralda in his projects

for the New

World Festival of the Arts in Miami in 1982.

Menus: Miralda, Sa Nostra-Caixa de Balears, Palma, Mallorca, 1995

(concept for book by Miralda in collaboration with Trasobares)

Essay appears on pages 16, 17; also in original Spanish version (pp. 18-19)

and in Catalan (pp. 13-15)

>>ELECTROLIBRARY<<